The Social Significance of the Eucharist in Early Modern Denmark

In many ways, the practice of the Eucharist in early modern Denmark was a feature of the efforts made to build stable communities. On the one hand, participating in the Eucharist was a way of affirming and protecting the community. On the other hand, social isolation and ultimately banishment was the harshest punishment a person who neglected the Eucharist could endure.

Church liturgy, legislation and disciplinary cases are sources with great potential for Danish historians and intellectual historians. However, I find the social imaginaries and practices contained in this form of source material to be highly interesting for understanding the social significance of religion in historical societies. In particular, I am interested in religion and theology not just as a theoretical system of thought, but also as lived religion within specific societies: as an integral part of how people understood and shaped their communities and interpersonal relations.

The Eucharist as social practice

Although Lutheran theology does not contain a specific social teaching, compared with other confessions, it does have a great number of social implications. For instance, Luther’s teaching of the three estates explained that the life of a Christian was characterised by three ‘relations’: to God (ecclesia), to the household (oeconomia), and to the temporal authorities (politia). All of these estates or orders carried individual as well as social duties and practices. The period of consolidation following the Reformation experienced a reemphasis on the social aspects of Christian life in an attempt to create stability, order and social coherence. The Eucharist was an important element in this endeavour, precisely because the Eucharist and the Baptism constituted the sacraments in which Christians established a community with Christ and their fellow Christians. In the Eucharist, the individual believers received the sacrament, which they could then carry with them in their community and everyday life. In many ways, the Eucharist became a social practice in which the local community congregated and found affirmation and identity.

Regna firmat pietas

Danish church history somewhat dubiously terms the seventeenth century and particularly the reign of Christian IV (r. 1596-1648) the Lutheran orthodoxy. In this period, particularly following the centennial year of the Wittenberg Reformation in 1617, political efforts to consolidate and build a coherent Danish Lutheran Church intensified. King Christian passed a number of church regulations aimed at disciplining and socialising both the clergy and lay folk into practising and keeping the true Christian faith. Church regulations and disciplinary control measures during these first decades of the seventeenth century reflected an attempt to root out unwanted forms of belief and behaviour and to improve the general quality and conditions of the clergy and church.

Sin as a crime against society

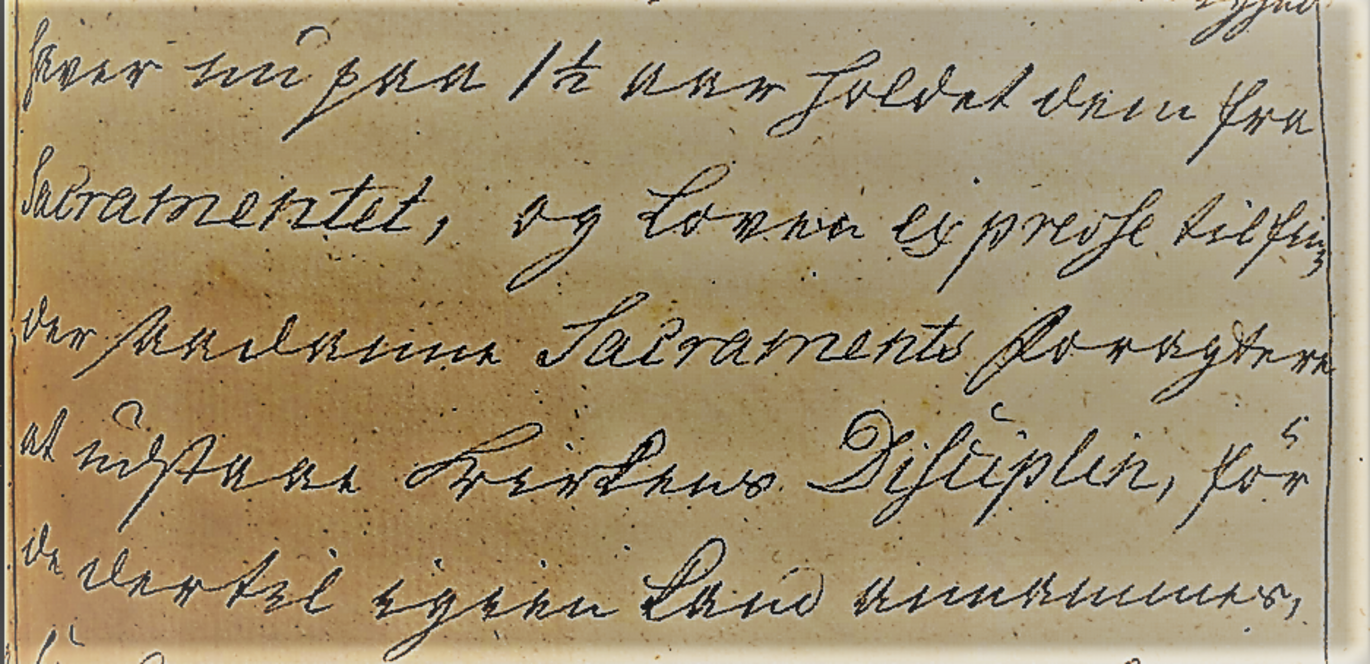

One of the many new church laws was the Forordning om Kirckens Embede oc Mendighed mod ubodfærdige, sampt om atskillige Geistlighedens Forhold [Ordinance on the office of the church and authorities against the irredeemable and also on several matters of the clergy] from 1629. This ordinance explained the authority and duties of the church and clergy in detail. Importantly, it gave the clergy authority to take up cases of moral corruption that would otherwise be difficult to pursue in temporal courts, such as neglecting sermons and the sacraments, abusing holydays, unchristian behaviour within marriage, drinking, cursing and gambling. Within contemporary social imagination, these endeavours were part of a divine battle between good and evil. As such, only a strong and pious Christian community could shield the realm against evil temptation and divine punishment. Sin was thus not only an individual matter, but posed a danger to the whole community. In this sense, the rise in the burning of witches and legislative measures against all forms of social deviants all reflected the criminalisation of anti-social behaviour.

Social isolation and banishment as punishment

Banishment served as the priests’ ultimate instrument of punishment against moral crimes, and the very threat of social exclusion was an important part of asserting moral discipline outside the temporal courts. Neglecting the Eucharist was a serious crime not only as a matter of individual faith, but also against the congregation as whole. It represented a dangerous form of anti-social behaviour, so it was the priests’ duty to reprimand and pursue persons guilty of such neglect. If private warnings proved ineffective, the priest could issue first a ‘small banishment’, which included a public identification of the guilty person followed by social isolation from the community. The church could literally exclude a person from any social interaction, deny them access to the sacraments, and physically separate them from the rest of the congregation during sermons. If these measures did not work, the church could issue a total banishment from the kingdom. Finally, if a person wanted to repent, they had to make a public confession in front of the whole community.

The Eucharist as a way of performing community

There can be no doubt that legally the 1629 ordinance gave the priests a formidable instrument of power. Of course, normative sources such as legislation tell us very little about the complexities and compromises of everyday life. Banishment cases represented a last resort towards those who stepped outside the norm. However, studies of landemode protocols indicate that this ordinance in general was relatively frequently (although unevenly) used.1 These cases have much to tell us about what contemporary social imagination deemed socially acceptable or inacceptable. It would be a reduction to view Christian IV’s church laws only as an attempt to impose top-down discipline and control. Reformation theology sanctified everyday life outside the church. This sanctification resulted in a renewed focus on community building and creating specific legitimate forms of sociality. The local community congregated in the Eucharist and for the congregation it manifested and affirmed their social relations and imaginaries. It was a way of building identity and shaping society.

This blog entry is based on my paper at Nordisk Historikermøde in Aalborg 2017 and is part of a larger research project called An economy of reception? The relation between sacrament and sociality in Lutheran Protestant societies at the LUMEN Centre, Aarhus University.

1Appel, Charlotte. Læsning Og Bogmarked I 1600-Tallets Danmark. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum, 2001, p. 127. Landemode protocols, church visitations and church books are sources revealing the practice of banishment and Eucharist, although preserved visitations are particularly doubtful sources.