How Did Lutheran Social Imaginaries Exert Influence on Danish Trust Culture during the Process of Democratisation?

The democratisation processes of Danish society in 1849 fuelled a crisis in the trust culture that hitherto had centred on the trustful relationship between loyal and obedient subjects and the absolutist king. This transformation of the trust culture was influenced by Lutheran social imaginaries transmitted by Grundtvig and the Grundtvigian movement. Af Sasja Emilie Mathiasen Stopa

‟We coped well with the pandemic, not least thanks to the basic trust of citizens in public authorities, which led us to being tested and vaccinated. This trust culture is unique and deeply rooted in the Danish associational – and educational – culture.” With these words, MP Bertel Haarder initiated his inauguration address to the Danish parliament in October 2021. He identified a causal relationship between Denmark’s remarkably high levels of social and institutional trust and the successful handling of the Covid pandemic. In his view, the Grundtvigian movement originally played a central role in developing this trust culture by fostering folk high schools and free schools and influencing the powerful Danish co-operative movement. In my current research, I examine Haarder’s contention that the Danish trust culture is rooted in Grundtvigian soil, as part of a much broader examination of the historical development of social and institutional trust in Denmark.

Lutheran Social Imaginaries of Trust

I analyse the role of social imaginaries pertaining to Lutheran theology in shaping Danes’ understanding of their social existence. As regards institutional trust, these Lutheran social imaginaries revolve around the encouragement of obedient trust in earthly authorities who act on behalf of God, and the assertion that ideal relationships between subjects and superiors depend on mutual, loving trust. Concerning social trust, Lutheran social imaginaries build on the view that all human beings are equal in relation to God, and as members of the priesthood of all believers, they are entrusted to take responsibility for their relationship with him without interference from ecclesial authority. Consequently, human beings should learn to read in order to obtain insight into their own faith. In Denmark in the 18th and early 19th century, these imaginaries were, inter alia, transmitted in the writings of the immensely influential minister, poet and politician N.F.S. Grundtvig and in the subsequent Grundtvigian movement.

Challenges to Trust Culture

My research focuses on three periods in modern Danish history in which the alleged trust culture was challenged by profound societal changes. First, the process of democratisation in the mid-18th century led to a break with the absolutist trust culture that had centred on loyal obedience towards hierarchically superior authorities, most importantly God and the king. Second, the threat and realisation of the German occupation of Denmark in the 1930s and 40s, as the Danish policy of co-operation with the German occupiers endangered Danes’ trust in the government. Third, the introduction of a genuine welfare state during the 1960s and early 70s; an expression of the homogenous Danish trust culture, which had equal rights to health care, education and social benefits as its founding feature. In this brief blog post, I highlight the crisis of trust inflicted by the process of democratisation and the role played by Grundtvig and the Grundtvigian movement in the attempt to overcome this crisis and reformulate social imaginaries of trust drawing on the Lutheran heritage.

The Fusion of National and Confessional Identities

Following the Danish Reformation in 1536, Denmark developed into a mono-confessional Lutheran state that incorporated the church. Up until the mid‐19th century, the absolute monarchy guaranteed a close connection between the church and the state, between national and confessional identity. This overlap between being Danish and being Lutheran was crucial for the cultural homogeneity that nurtured social and institutional trust. However, with the Constitutional Act of 1849, Denmark became a constitutional monarchy and a parliamentary democracy, and freedom of religion was gradually implemented. National and confessional identity were legally separated, paving the way for a secular society. Informally, though, Lutheran theology remained a steady influence on Danish society long into the 20th century, not least through the influential popular movements of Grundtvigianism and the Inner Mission, which stood at the core of the organisational society that developed in the late 19th century.

Democratisation as a Threat to Danish Trust Culture

The transition to a modern liberal democracy elicited the upheaval of the hierarchical social structures of feudalism. These were replaced by relations between democratically elected authorities and citizens who shared equal rights irrespective of their social background. This shift had profound consequences for Danish trust culture, as it challenged the perception of trustworthy authority. Grundtvig acknowledged this challenge and warned against introducing parliamentary democracy in several of his writings in the 1830s and 40s, as he believed it would threaten the trusting relationship between the absolutist king and his people. Hence, in The Danish Four‐Leaf Clover, Or A Partiality for Danishness from 1836, Grundtvig celebrates this relationship as the foundation of Danish society: “… here, king and people have nothing else to quarrel about than the level of generosity, but everything to compete for in order to show the world, who is best at honouring and using that immeasurable gift, most clearly vindicating the mutual, outside of Denmark unique, fatherly as well as childish, trust!” Grundtvig agrees with Luther in depicting the ideal relationship between subjects and superiors as a reflection of the relationship between God the father (or any kind of parental authority) faithfully caring for his children, and the children showing trustful obedience to him.

Grundtvig, however, explicitly grants the children freedom of speech. Moreover, he introduces the concept of the “school for life” and the idea of the folk high school, which was ground-breaking for promoting adult education, turning the sons and daughters of the peasantry into trustworthy democratic citizens who could make their voices heard. In my view, this emphasis on the need for enlightenment is rooted in Luther’s understanding of individuals as members of a common priesthood authorised to read and interpret the Bible. Grundtvig knew this incentive from his upbringing in a pietistic minister’s home as well as from his theological studies at Copenhagen University, which at the time was influenced by rationalism.

Paving the Way for a Democratic Trust Culture

On the one hand, Grundtvig spoke against endangering the trust relation between the king and his people and maintaining loving trust as “the inherited characteristic of all true Danes” (Kort Begreb af Verdens Krønike i Sammenhæng, 1812). On the other hand, he was pivotal in paving the way for a new democratic trust culture by emphasising the need for adult education, which could turn simple peasants into trustworthy citizens capable of taking on responsibility as a legitimate authority. “The age of rank is over, now the age of the people must come” (“Overgangs-Tiden i Danmark II”, Danskeren, 1849). In this way, Grundtvig accentuates the transitional period around 1849, which he describes as a slow coming-of-age process for the Danish people: “… for just as Rome was not built on one day, an entire people, although born on a single day, is unable to grow up immediately.”

Inventing Modern Figures of Authority

The change of political system resulted in the people replacing God and the monarch as sources and main figures of authority. Authorities no longer held divinely sanctioned offices or carried the “masks of God”. As a result, there was a need to redefine legitimate and trustworthy authority as part of a new democratic trust culture. Together with other social organisation movements, such as the labour movement, the women’s movement, and the Inner Mission, the Grundtvigian movement became crucial in defining new figures of authority who could take on leader roles in the organisational society that took shape from the late 19th century onwards. One of the earliest of such figures was the teacher. Another figure was the local manager of the consumer co-operative, who sold the various products produced by the increasingly powerful co-operative movement.

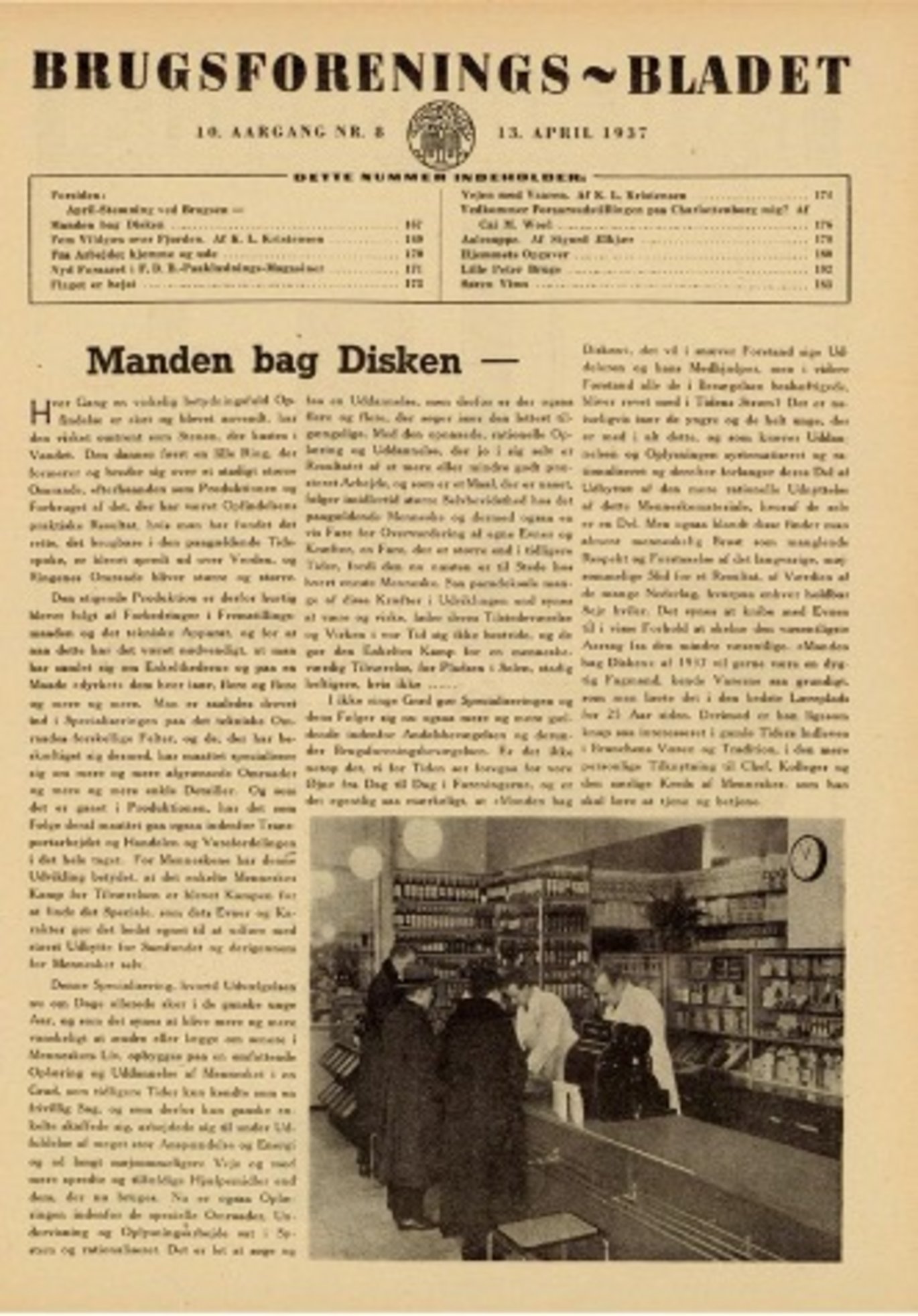

In a 1937-article from the co-operative movement’s magazine, Brugsforenings-Bladet, this manager, or “the man behind the counter” as he is called, is described as a loyal servant of the co-operative society and of society as a whole. The consumer co-operatives were built by the older generation using “the only truly sustainable means, namely mutual trust. Trust among the members themselves and between the members and ʽthe man behind the counter’”. The article describes the trust culture by having recourse to agricultural metaphors: “But the course of life revealed how in the field fertilised by mutual trust, constituted by the steady and loyal member circle, the seeds of competence, expediency and service sprouted the most and gave the best result.”

This suggests that trust remained a defining characteristic of Danes in “the age of the people”. However, it was no longer a childish and obedient trust in God and the king, but an enlightened, mutual trust among mature citizens who acknowledged new democratic figures of authority as trustworthy.

Literature:

‟Den tillidsvækkende Grundtvig: Kærlig tillid som danskernes arvelige kendemærke”, in: Den store mand: Nye fortællinger om Grundtvig, Lone Kølle Martinsen (red.), København: Gads Forlag, 2022, 236-253.

“Den kristne opdragelse i 1700-tallets Danmark”, in: Pligt og omsorg – velfærdsstatens kristne kulturarv, Bo Kristian Holm & Nina Javette Koefoed (red.), København: Gads Forlag, 2021, 105-133.

“Trusting in God and His Earthly Masks. Exploring the Lutheran Roots of Scandinavian High-Trust Culture”, Journal of Historical Sociology 33:4, 2020, 456-472.